QUESTION: Using specific art references, why did the Greeks consider "beauty" to be the same as "truth" and how different was this philosophy from that of the Romans?

PART 1

Summary

At first after choosing this question, I really didn't know where to go with it. I was interested, certainly, but it seemed so much more general than my previous questions. I suppose it was all challenges until I got my book out and picked my quotes. Once I knew what needed to be said, everything flowed.

Reason

For one thing, this is a question that we spent a lot of class discussing. Truth and perception is vital to the study of art history. Some things must be seen with the lens of the time period, rosy or crystal clear. As a student in this course its important to remember that my version of truth or even just my aesthetic isn't the only solution to the visual problem.

Purpose

I believe the purpose behind this question was to really delineate the confusing space that is Greco-Roman art. We see them as practically the same thing throughout early education, for sure. This question forced me to look at their differences, and in the process gave me a real insight on the mindset of the ages.

Direction

I think I changed opinions during this essay a few times. As an artist myself, I cant deny idealizing forms in some sense repeatedly through my work. Yet, I kind of found it silly at one point when stewing over Greek idealism. On the other hand, is reality really what I want to show people in art, where I have total freedom over the (intended) impression?

Impressions

I think the quote at the end of the essay was a big, pivotal realization for me. After thinking so much on what truth now, I felt like I was in high school again and back in my philosophy club, where there was never an answer to anything. Not really the best idea for someone with anxiety in the first place! It was freeing for me to remember that regardless of the truth that ascends above and beyond all that I can see and hold, the perceptions that people like you and me, and even the Romans and Greeks, continually make and reform are what really matter in our day to day lives.

PART 2

If you've taken even one philosophy course, you're sure to have heard that "truth is subjective." Each person to ever live has a truth that is specific to him or herself. We cannot truly put ourselves into someone else's perspective or see the world from their truth, nor can we assume to speak for any collective vision. This essay attempts to speak for a long-dead peoples' version of truth, so although it is a bit contradictory to say in an academic paper, please bear in mind that this is no more than an informed opinion on opinions. That said, what did the Greeks mean by "beauty is truth" and how does this relate to the Roman idea that "truth is reality" in an artistic context?

Pablo Picasso once stated, "We all know that art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth that is given us to understand. The artist must know the manner whereby to convince others of the truthfulness of his lies." (lecture notes) Like Picasso, Greek artists from the Archaic period into the Classical period and beyond attempted, quite successfully, to convince their patrons of the truth they executed. But, is this truth the factual version of the subject matter portrayed? They were fantastic artisans, to be sure-- my favorite works are usually their sculptures (even if they're mostly copies). The beautiful pieces they created and their artistic skill never ceases to amaze, and regardless of if the versions we study are casts or not, the level of detail and realism can be incredible. One particularly stunning work is the Medici Venus.

|

| Source Medici Venus Marble sculpture Made by an unknown artist of the Praxitelean tradition 1st century BC |

So, if they could show the actual form, why idealize? Like our text author Marilyn Stokstad writes, they were certainly capable. What makes the idealization better than reality? How can we call that truth? In some ways, showing the beauty of the possible rather than finding the beauty in the actual is rather romantic. It offers a slight disconnect and removes some accessibility from the art-- whomever is being depicted now becomes a character rather than a (likely) flawed human being. They can now represent more than just themselves. This is, of course, wonderful in cases of gods & goddess subjects. The story is enhanced in these cases, and fit that ascendent life in their perfection. In portraiture, it seems a bit confusing to me. If you want to make your mark on the world, wouldn't you want the factual truth to face the ages?

Plato's opinion was a big NO. Stokstad writes “Plato looked beyond nature for a definition of art. In his view, even the most naturalistic painting or sculpture was only an approximation of an eternal ideal world in which no variations or flaws were present. Rather than focus on a copy of the particular details that one saw in any particular object, Plato focused on an unchangeable ideal-- for artists, this would be the representation of a subject that exhibited perfect symmetry and proportion. [...] To achieve Plato's ideal images and represent things "as they ought to be" rather than as they are, classical sculpture and painting established ideals that have inspired western art since." (text, xxxiv)

Beauty, to the Greeks, was the truth. Beyond what we can see in front of us, there is the ideal that could stand the test of time and deliver the truest perfection. To the Greeks and Plato specifically, that which we see is just as much a representation as the art we create. In the words of Aristotle, “the aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance.” Artwork like the Medici Venus showed a universal mold. Regardless of whatever the posing model may have looked like, the Venus' outward beauty and idealization is the ultimate female figure personified.

The “perfect” figure we see most of all comes from around 450 BCE. “Just as Greek architects defined and followed a set of standards for ideal temple design, the sculptors of the classical period selected those human attributes they considered the most desirable, such as regular facial features smooth skin, and particular body proportions, and combined them into a single ideal of physical perfection. The best known theorist of the classical period was the sculptor Polykleitos of Argos.” (text, 128) He wrote and even sculpted an example of what he declared as The Canon, a perfected measure of human proportions. (text, 129)

|

| Source The Doryphoros Lost bronze original, marble copy Polykleitos Approx. 450-400 BCE |

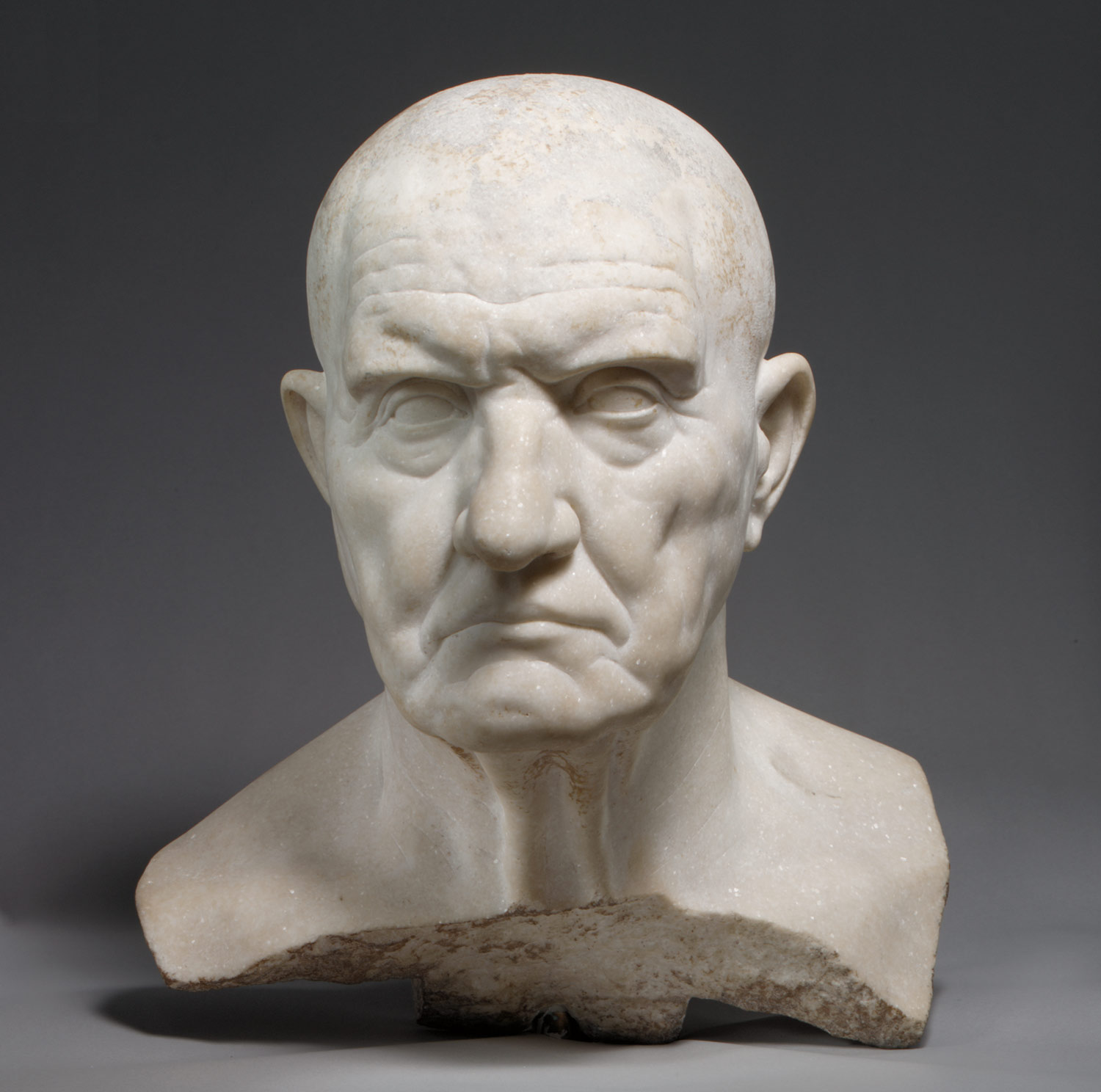

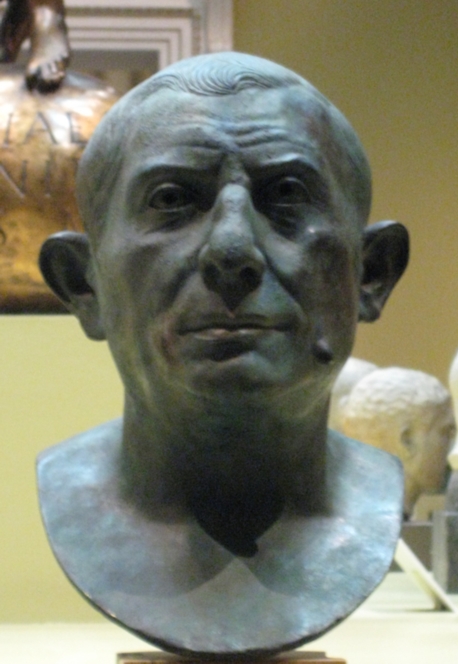

"Sculptors of the Republican period sought to create believable images based on careful observation of their surroundings. The desire to render accurate and faithful portraits of individuals may be derived from Roman ancestor veneration and the practice of making death masks of deceased relatives. Roman patrons in the Republican period clearly admired realistic portraits..." (text, 180)

It is indeed the portraiture in this case that most fully shows this trend. Unlike the Greek art, where portraits of official figures was hardly more than a loose representation of what the politician or patron looked like, in Roman art we can see the person as they were, as if to come alive. Similarly skilled, the portraits of state, which were more intended for PR than anything else, give us these long dead men and woman, flaws and all. “In the Republic, the most highly valued traits included a devotion to public service and military prowess, and so Republican citizens sought to project these ideals through their representation in portraiture. Public officials commissioned portrait busts that reflected every wrinkle and imperfection of the skin, and heroic, full-length statues often composed of generic bodies onto which realistic, called "veristic", portrait heads were attached.” (http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ropo2/hd_ropo2.htm#top)

|

| Source Portrait Bust of a Man Marble Artist Unknown 1st century BC |

|

| Source Lucius Caecilius Jucundus Bronze Artist Unknown Found in Pompeii, date of origin unknown |

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteMac - Bet you never thought your philosophy class would come in handy. The pat answer to this question is usually cited from John Keats Ode on a Grecian Urn - "Beauty is truth, truth beauty" and the famous quote, "...beauty is in the eye of the beholder" really. Both Epictetus and the now classic Rolling Stone ad campaign slogan - perception is reality are correct - change the perception and along with it goes the reality. Or, as I once wrote here - http://rfortier.blogspot.com/2012/04/really-my-reality-may-not-be-yours-but.html I'll give you a 3.8 for this one!

ReplyDelete