QUESTION: Is Art in any way, an intrinsic part of, or a primary factor in religion or religious expression and if so, how did it specifically play a part in the development of Christianity?

PART 1

Summary

I actually really enjoyed the research for this essay. It's all pretty loose and less specifically factual than my last essay, which was nice in comparison. Not to say it isn't the truth I've written! Just that there are less dates and people involved in the discussion. I had some trouble with the actual essay though. I wrote most of it at school last week but when I saved it on my flash drive it got corrupted, so instead of just finishing it up on Friday morning and uploading it before I had to work at 10, I had to re-write the whole thing. Luckily I still had my research sources or I would have been a lot worse off. Perhaps that's why the research was the best part for me?

Reason

This question was asked so that I would explore the meaning behind art-- not just the contextual understandings of any piece of work, but the real drive behind art as a tool.

Purpose

I think this question was asking me to really think about art as a tool, but more than that, how it can shape a religion or religious practice.

Direction

For this essay, the direction I took was mostly on devotional imagery and it's place in the practice of Christianity. I also looked at the adoption of symbols from other traditions, like how Christmas is really placed on a pagan holiday, which made it more acceptable for the early Christians to celebrate.

Impressions

I'm left after writing this essay thinking a lot about the rosary and sand mandalas. Also, illuminated manuscripts, which I didn't mention in the essay proper. It was all rather interesting to look into. As someone who isn't religious (I identify as agnostic atheist, but only if asked) it was a different sort of experience thinking about how religious images can move people. But then I thought about my recent tattoos, and I remembered why I got them--part as remembrance of the me at this moment, yes, but a lot of the reason was my devotion to the games from which the symbols came from. That, in it's own was, sort of relates to how anyone could wear a cross pendant day in & out, albeit in a more permanent way. Anyhow, enjoy!

PART 2

Art existed in various forms well before religion as we know it today came to be. Whether it was simply representational of what early peoples saw in their day to day life, or some sort of response to questions on higher involvement or the meaning of life, art has always served a purpose. Of course, aesthetic or emotional release are also purposes that art can be created for. While we can appreciate art regardless of whatever reason it was created for, I believe that the advancement of religion, specifically Christianity, can not be looked at without acknowledging the importance of art in it's development.

Christianity in particular owes much to art. As a more recent religion (if you can say that about 2k years) we can trace the physical evidence with much less issue. It also helps that art gained more validity as time went on. I think Christianity and art meet up at the perfect time in both their developmental paths. For one thing, it's important to note that Christianity was not accepted as a major religion for quite some time. It wasn't until the year 313, when Constantine I issued the Edict of Milan, that Christians could worship freely.

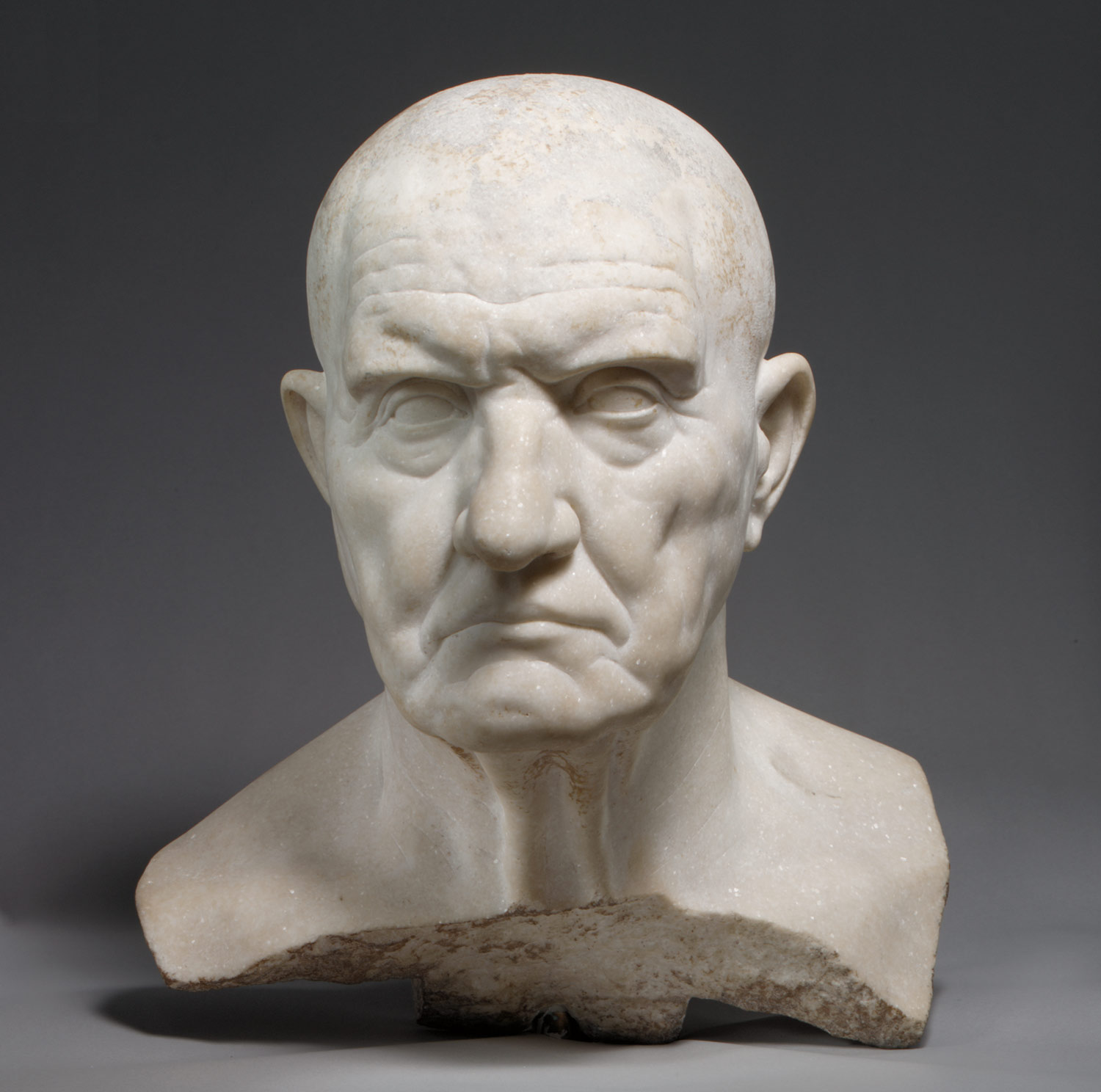

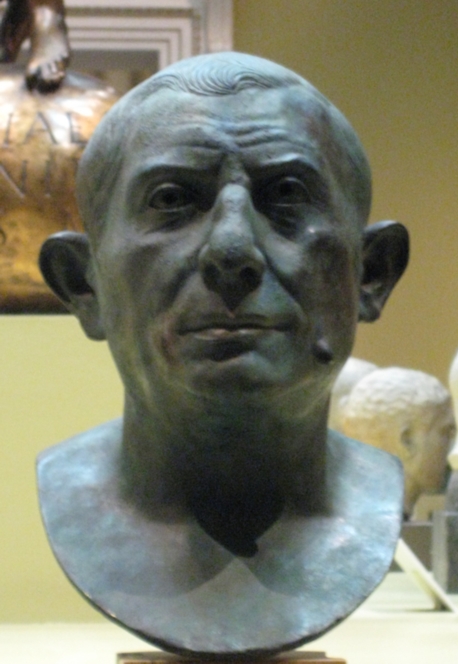

The new religious tolerance does not exactly mean acceptance or world domination yet! But more key is the evolving of Christian art in secret or alongside the pagan and Jewish traditions. “Symbols have always played an integral role in Christian art. Some were devised just for Christianity, but most were borrowed from pagan and Jewish traditions and adopted for Christian use.” (Text, pg 238) Anything worth following is generally going to have a symbol to go alongside it, to stand for every message that would take too long to write out (or, for the earlier times, for less literacy in common-folk). More than that, though, symbols are powerful tools-- take the Swastika of the Nazis, or the hammer and sickle of the Communist party. Or, for a less tyrannical example, any flag or logo out there, like the Red Cross' eponymous symbol. For Christians, it would be the dove, the lamb, the fish, and monograms among other things, but most importantly was of course the cross. The Evangelists have their own associated animals too. For example, Mark was often seen as a winged lion. I think I spot him in the upper left hand corner of the below image of Orpheus, in fact.

|

| Source Orpheus from Aegina marble statuette unknown artist 4th century |

“Christians began to use the visual arts to instruct worshipers as well as glorify God. Almost no examples of specifically Christian art exist before the early third century, and even then it drew it's styles and imagery from Jewish and classical traditions. In this process, known as syncretism, artists assimilate images from other traditions and give them new meanings. The borrowings can be unconscious or quite deliberate. For example, orant figures—worshipers with arms outsretched—can be pagan, Jewish, or Christian, depending on the context in which they occur. Perhaps the most important of these syncretic images is the Good Shepard. In pagan art, he was Apollo, or Hermes the shepherd, or Orpheus among the animals. He became the Good Shepherd of the Psalms and Gospels to the Jews and Christians.” (Text, pg 239)

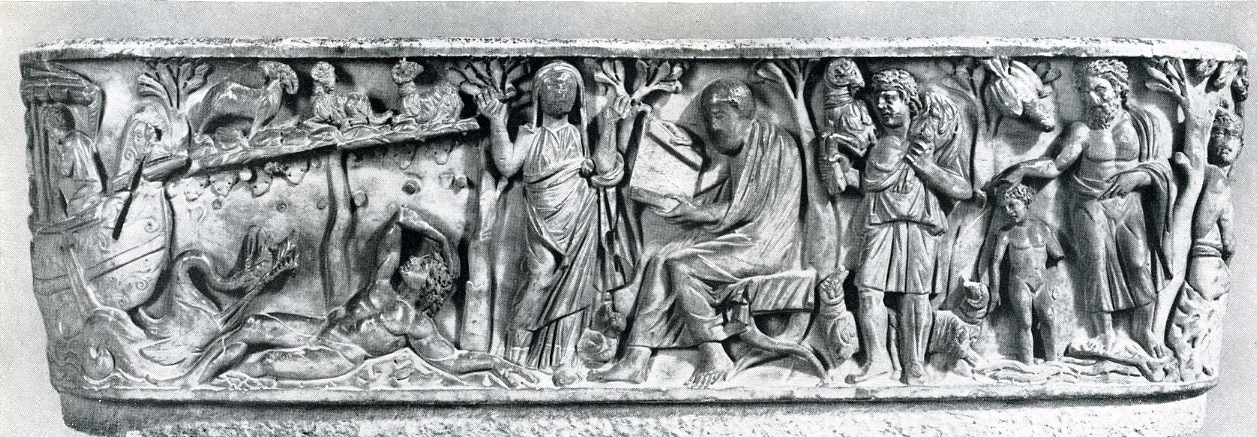

In another pertinent example, the Sarcophagus of the Church of Santa Maria Antiqua in Rome shows an image that any viewer, regardless of creed, could accept:

“The subject of the sculpture would be appropriate for either a pagan or Christian family […] Nothing represented here could offend pagan sensibilities. But to the informed Christian, the orant is the Christian soul, the seated man is the teaching Christ, followed by Christ the Good Shepherd and a scene of baptism. The sleeping youth is Jonah, resting after his ordeal, and the monster is the classical form of a dog-headed serpent.” (Text, pg 241)

|

| Source Sarcophagus of Santa Maria Antiqua marble(?) unknown artist c. 270 |

"Not surprisingly, Christianity has extended its influence to many works of Western art. Artists use their artworks to express their own faith or to describe Biblical events and views on Christianity. Often, their works are designed to have a special effect on the viewer. Some works of art are devotionals, designed to make the viewer think deeply about faith and beliefs. Other works are intended to teach the viewer. Some works are dramatic and emotional, used to make the viewer feel a sense of love, fear, or respect for Christianity. And some artworks are used in Christian rituals." (http://www.artsmia.org/world-religions/christianity/)

Personally, when it comes to art, I enjoy a good story mixed with some nice aesthetics. Though I am not Christian or religious in any twist of the meaning, I'll admit that the 'stories' found in the Bible, or in any religion's holy book(s), are fascinating to say the least. Like above stated, art could be used to tell these stories, or to express a personal faith. It could be used to teach or evoke emotion or thought. The most vital in terms of art's role in advancing the religion is the use as a devotional tool.

Devotional images are defined as the “isolation of a holy image from a narrative context in order to promote spiritual contemplation and prayer.”(http://arthistory.about.com/od/glossary_d/a/d-devotional-image.htm) Basically, they serve to give rise to religious thought. Icons of Jesus or Mary, or any of the saints, have inspired millions of devotees. Take any person you've seen with a cross necklace, and that's a fine example. I think, partially due to the timing and prior development of the arts, that Christian art works incredibly well at it's intended goal. Like we've repeatedly discussed in class, iconoclasms occur because these images are so evocative for either devotion, as was intended by early Christians, or the rage that fuels one to destroy art, surely not intentional.

Although he was writing more to note how art has lost it's integral part in our culture in more recent years, I feel that Dewitt Parker hits the significance of devotion in this quote: "In subtle ways, the influence of art, while remaining indirect, may affect practical action in a more concrete fashion. For silently, unobtrusively, when constantly attended to, a work of art will transform the background of values out of which action springs. The beliefs and sentiments expressed will be accepted not for the moment only, aesthetically and playfully, but for always and practically; they will become a part of our nature. The effect is not merely to enlarge the scope of our sympathies by making us responsive, as all art does, to every human aspiration, but rather to strengthen into resolves those aspirations that meet in us an answering need. This influence is especially potent during the early years of life, before the framework of valuations has become fixed. What young man nursed on Shelley's poetry has not become a lover of freedom and an active force against all oppression? But even in maturer years art may work in this way. One cannot live constantly with the “Hermes” of Praxiteles without something of its serenity entering into one's soul to purge passion of violence, or with Goethe's poetry without its wisdom making one wise to live. The effect is not to cause any particular act, but so to mold the mind that every act performed is different because of this influence.

|

| Source Sand Mandala colored sand Namgyal monks (recent, no date given) |

It's not to say that without art, Christianity would not exist today. But I do think Christianity as we know it would not be here in the same form. One of the most notable things about Christianity in the study of art history is the sheer prevalence of Christian imagery throughout the times. No matter the period, I'm sure you can find some Christian iconography or even simply the multitude of biblical scenes portrayed by thousands of artists over time. Just as Christianity pervades art, so does art penetrate the Christian experience.